News

Ecuador’s culinary identity at Madrid Fusión for the first time

Juan Sebastián Pérez currently runs “Quitu, Identidad Culinaria”, a space where he promotes the biodiversity of his country, Ecuador; the richness of its products and his work with small-scale farmers. Today he presented it all at Madrid Fusión.

Juan Sebastián Pérez runs the Quitu Identidad Culinaria restaurant in Toledo (Quito, Ecuador), where he promotes his country’s gastronomic culture. At Madrid Fusión he served up Ecuador’s culinary identity and the national pantry in three recipes featuring autochthonous products, some of which are varieties that have been recouped. “This is the first time a chef from Ecuador has been on stage at Madrid Fusión, and let’s hope it’s not the last”, says Ignacio Medina, presenter of the talk, who did not hesitate to define him as “the leading representative of the new wave of Ecuador chefs”.

Juan Sebastián Pérez began his talk by explaining that his restaurant has expanded on the guiding principle of identity, the people who stock his pantry, and the local raw materials the land gives them. Like most, Juan Sebastian was not spared by the pandemic: “in view of the conditions following the pandemic, my dedication to cooking is absolute. We have a sampling menu with the products we bring in such as maize or potatoes, tubers, what the land gives us … and we have an eight-dish sampling menu which we change every day”. The restaurant can seat 15 diners. He adds: “our work is the work of communities, and I explain their history at my restaurant”.

The chef came up with three recipes to showcase the culinary identity which lays down the restaurant’s philosophy.

The first is black native papa potatoes (“puca shungo”), which are “rich in valuable antioxidants and nutrients”, says the chef. This is a variety that had fallen into disuse a few years ago. Mechanical ploughs on the land destroyed them, they were left to rot, and never made it to the market. “We began to work with them, and replaced the mechanical ploughs with manual equipment. We brought in a lot of produce which we stored in straw. The peasants let the papas age because there are only two harvests a year. When the papas wrinkle and turn ugly like that, they’re ready for eating”. These potatoes are used as the basis to produce a cake with this tuber, with a soft texture inside and crunchy outside. This is accompanied by white cocoa (“macambo”), and a pesto with a variety of beetles known for their high energy potential. “The peasants keep these beetles in their pockets to eat them during the day out in the fields”, says Juan Sebastián.

The second recipe is a “cui” terrine. This is a very common local animal, with which they have developed “a spectacular value chain by changing to a more natural diet”. He makes a confit of the animal in its own stock to use 100% of the product (the bones and skin are part of the recipe, and the “innards” are used to make a pâté). This is accompanied by Andes tubers (“mashua”), a demiglace, carrots and preserves pickled in maize vinegar (known as “chichagre”). Many of these products, like the black papas, have been recouped and gradually added to the market. “They are now being sold as the public at large begins to ask for them”, explains the chef.

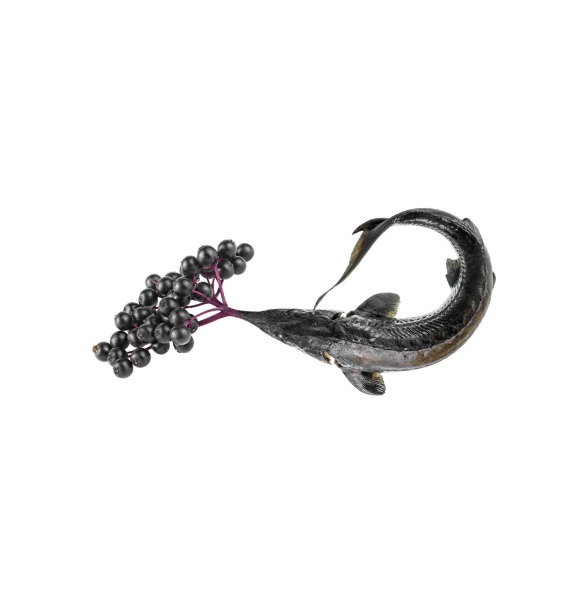

The third and last dish is a llama sirloin steak tartare. “The Andes soil is nutritious, with a large amount of minerals, many different varieties, and very fertile, providing llamas with food to make their bodies lean and add to the value chain”. He adds: “These animals go around in herds, and there is a large amount of responsibility and sensitivity with them”. The chef then praises the work of the butcher. “A butcher’s work is one of the most talented professions, because he can provide up to eight different cuts, and we can use the entire animal”. He adds vanilla to the meat. Amazon vanilla differs from others in that its fragrance is fruitier, more like citrus, and more exotic. “The peasant who grow these pods cover them with leaves, not plastic, they taste different, and provide a higher yield”, says the chef. Production at his restaurant could be defined as a mise en place and instant cuisine. “I like to customise the menu of each diner. And that shields me from any disasters,” he adds. He continues the recipe with a distillate of agave, a typical product of Ecuador. He finishes it off with “capulí” – “it isn’t a berry, even though it looks like one, it’s a fruit”, says Pérez, “it has an earthy taste, slightly bitter but not acidic, and this brings out the flavour of the llama tartare”. And ají peppers. There is a huge amount of ají peppers, but they prefer to be guided by their sweet taste, and how they can be enjoyed on the palate without “locking out” the taste buds. They are usually hung up in storage, and then they are cooked in stews so that they do not dry out, and then they are hung up again. “This ají would have been in quite a few stocks”, he says. He adds some vegetable caramel to the dish along with some shoots.

.jpg)